Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: Roberto Nickson

Photo: Roberto Nickson

But musicians usually don't want to talk about wavelengths and frequencies. Instead, they just give the different pitches different letter names: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. These seven letters name all the natural notes (on a keyboard, that's all the white keys) within one octave.

Practicing the five shapes in various positions along the fretboard will develop your vocabulary of sounds and give you more room to...

Read More »

Pianists usually sit at the edge of the piano bench to allow their legs to comfortably use the pedals. Sitting at the edge of the piano bench...

Read More »

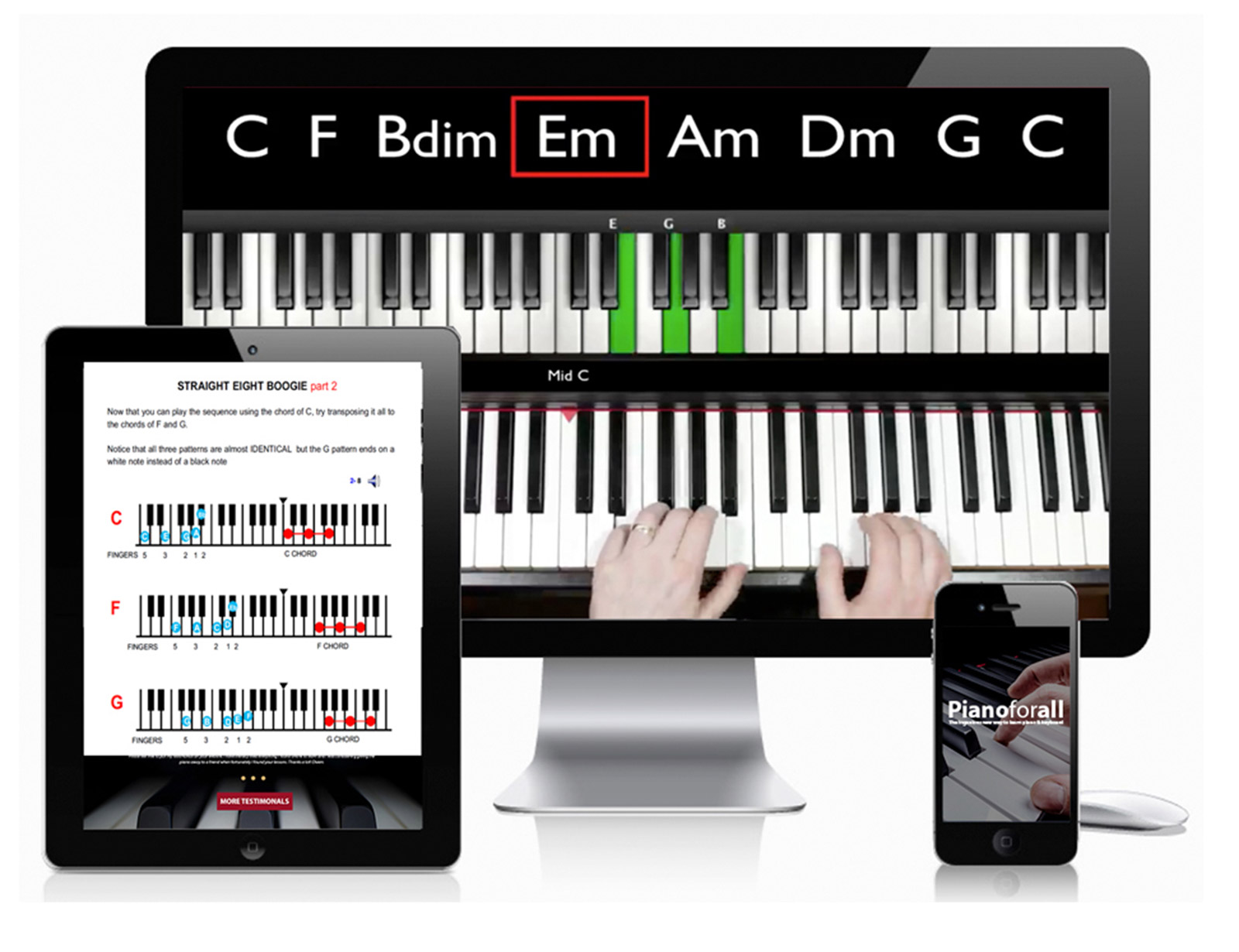

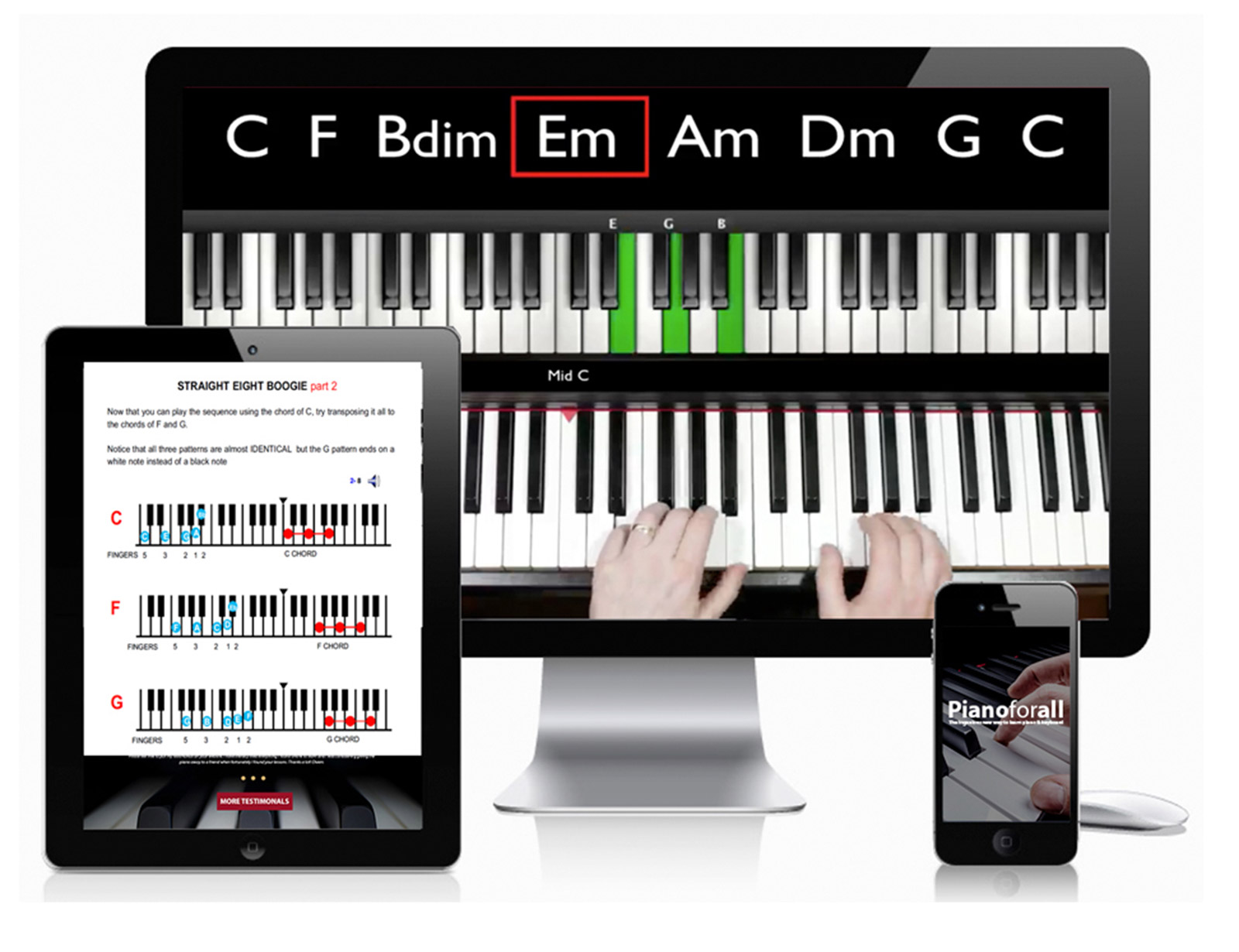

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

Here's how you can become a millionaire in five years or less. Select your Niche. ... Put aside 20% of your income every month. ... Don't spend...

Read More »

The 10 Most Popular Musical Instruments Piano/Keyboard. Some experts separate the two, and they do have different uses, but the basics are very...

Read More »Much more common is the use of a treble clef that is meant to be read one octave below the written pitch. Since many people are uncomfortable reading bass clef, someone writing music that is meant to sound in the region of the bass clef may decide to write it in the treble clef so that it is easy to read. A very small "8" at the bottom of the treble clef symbol means that the notes should sound one octave lower than they are written. Figure 1.9. Why use different clefs? Music is easier to read and write if most of the notes fall on the staff and few ledger lines have to be used. Figure 1.10. The G indicated by the treble clef is the G above middle C, while the F indicated by the bass clef is the F below middle C. (C clef indicates middle C.) So treble clef and bass clef together cover many of the notes that are in the range of human voices and of most instruments. Voices and instruments with higher ranges usually learn to read treble clef, while voices and instruments with lower ranges usually learn to read bass clef. Instruments with ranges that do not fall comfortably into either bass or treble clef may use a C clef or may be transposing instruments. Figure 1.11. Exercise 1.2.1. (Go to Solution) Write the name of each note below the note on each staff in Figure 1.12. Figure 1.12. Exercise 1.2.2. (Go to Solution) Choose a clef in which you need to practice recognizing notes above and below the staff in Figure 1.13. Write the clef sign at the beginning of the staff, and then write the correct note names below each note. Figure 1.13. Exercise 1.2.3. (Go to Solution) Figure 1.14 gives more exercises to help you memorize whichever clef you are learning. You may print these exercises as a PDF worksheet if you like. Figure 1.14.

Take your first (index) finger on your fretting hand and hold it at the fifth fret on the third string. Then hammer on your second (middle) finger...

Read More »

Giant Vizsla What dog breed is Clifford? Clifford is a Giant Vizsla. Although Clifford is over 10 feet tall and weighs A LOT (we don't know exactly...

Read More »

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »Notice that, using flats and sharps, any pitch can be given more than one note name. For example, the G sharp and the A flat are played on the same key on the keyboard; they sound the same. You can also name and write the F natural as "E sharp"; F natural is the note that is a half step higher than E natural, which is the definition of E sharp. Notes that have different names but sound the same are called enharmonic notes. Figure 1.22. Sharp and flat signs can be used in two ways: they can be part of a key signature, or they can mark accidentals. For example, if most of the C's in a piece of music are going to be sharp, then a sharp sign is put in the "C" space at the beginning of the staff, in the key signature. If only a few of the C's are going to be sharp, then those C's are marked individually with a sharp sign right in front of them. Pitches that are not in the key signature are called accidentals. Figure 1.23. A note can also be double sharp or double flat. A double sharp is two half steps (one whole step) higher than the natural note; a double flat is two half steps (a whole step) lower. Triple, quadruple, etc. sharps and flats are rare, but follow the same pattern: every sharp or flat raises or lowers the pitch one more half step. Using double or triple sharps or flats may seem to be making things more difficult than they need to be. Why not call the note "A natural" instead of "G double sharp"? The answer is that, although A natural and G double sharp are the same pitch, they don't have the same function within a particular chord or a particular key. For musicians who understand some music theory (and that includes most performers, not just composers and music teachers), calling a note "G double sharp" gives important and useful information about how that note functions in the chord and in the progression of the harmony. Figure 1.24.

They wrongly assume that if you don't start when you're very young, that learning violin will be too difficult. Nothing could be further from the...

Read More »

A new study from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital at McGill University found that listening to highly pleasurable music releases...

Read More »

You can also look to the melody of a song and notice where it ends. Melodies typically resolve to the tonic note of the key. Again, if a song's...

Read More »

Joy Chapman certainly knows how to “drop it low” - using her powerful voice! The vocalist from Surrey, British Columbia, Canada has officially...

Read More »