Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: Alina Vilchenko

Photo: Alina Vilchenko

The idea behind twelve is to build up a collection of notes using just one ratio. The advantage to doing so is that it allows a uniformity that makes modulating between keys possible.

Skoove is an app that offers hundreds of piano lessons for players of all skill levels. While it's best suited for teens and adults, younger kids...

Read More »

Yes, you can play the piano with long nails, but playing becomes more difficult. Long nails can cause a knocking noise on the keys and force you to...

Read More »

What is this? The most common keyboard sizes are Full-Sized (104 key), TKL (87 key), and 60% (68 key). Each size is unique with different features....

Read More »

Kawai pianos offer a warmer, fuller quality of tone when compared to a normal piano built by Yamaha. This has made them the preferred choice of...

Read More »Unfortunately, no one ratio will do the trick exactly. However, the ratio of 3/2 happens to work reasonably well using 12 steps. With 3/2 as the basis for the scale, none of the above ratios besides a unison, fifth, and major 2nd are captured exactly. However the most important constraint- namely that we get a repeating pattern going up in octaves, is almost satisfied by this scheme. Namely, after 12 applications of the ratios 3/2, we come back very close to where we started from (always dropping down by an octave, i.e. dividing by 2, each time the ratio exceeds 2): (3/2)^0 = 1 (3/2)^1 = 1.5 (3/2)^2 = 1.125 (after dividing by 2) (3/2)^3 = 1.6875 (after dividing by 2) (3/2)^4 = 1.2656 (after dividing by 4) (3/2)^5 = 1.8984 (after dividing by 4) (3/2)^6 = 1.4238 (after dividing by 8) (3/2)^7 = 1.0678 (after dividing by 16) (3/2)^8 = 1.6018 (after dividing by 16) (3/2)^9 = 1.2013 (after dividing by 32) (3/2)^10 = 1.8020 (after dividing by 32) (3/2)^11 = 1.3515 (after dividing by 64) (3/2)^12 = 1.0136 (after dividing by 128) The chromatic scale reflects this fact. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the chromatic scale was tuned using the idea of 3/2. In the most elegant of these, Thomas Young's tuning, several of the fifths were set exactly to 3/2, and the others were tempered slightly (to make octaves exact). In the modern equal temperament (which came into practical use during the early part of the 20th century), all fifths are tuned to 2^(7/12)=1.49651..., slightly less than 3/2, and 12 repetitions of this ratio gets us back to where we started (after dropping down 7 octaves). Between the two methods of incorporating 3/2, the former gives the various keys character, and I prefer it highly. See the essay I wrote on this. Of the various intervals, the only ones that are really well captured by tempered versions of the 3/2 scheme are: unison, 5th, major 2nd, and their reciprocals (octave, 4th, minor 7th). Two questions: why 3/2? The choice of 3/2 says that, next to the octave, it should be regarded as the most important interval. One can also use a major 3rd (i.e. ratio of 5/4) to build up a scale. This is discussed towards the end of this essay. Why do 12 steps work nicely? Interestingly, this can be explained in terms of simple number theory, namely continued fractions. We want to understand when a power of 3/2 will be close to a power of 2:

He wants to buy land in Mississippi where his family was once enslaved. Berniece refuses to sell the piano, because it represents the family's...

Read More »

A preference for instrumental music indicates higher intelligence, research finds. People who like ambient music, smooth jazz, film soundtracks,...

Read More »If one, similarly, forms the continued fraction for log(5/4)/log(2)=.32192809..., one finds the following list of approximating fractions: 1/3, 9/28, 19/59, 47/146, etc. This suggests, for example, that a 28 note scale would work nicely using the major 3rd as the basis for its construction. On the other hand, we need not always work with the best. For example, 11/19 = .5789... is reasonably close to log(3/2)/log(2) = .5849..., and 6/19 = .3157... is reasonably close to log(5/4)/log(2)=.3219.... This suggests that a 19 note scale with a major 3rd being 6 'semi-tones' and a perfect 5th being 11 'semi-tones' might work nicely. In fact, 19 appears in the denominators of rational approximations of the continued fractions for log(5/3)/log(2), and log(6/5)/log(2). This says that 19 would also work well for capturing the reciprocal pair of ratios 5/3 and 6/5. If we use an equal tempered 19 note scale, we get the following list of ratios k/19 k 2 nearby ratio --- --------------------- ----------------------------------- 0 1 unison * 1 1.0371550444461919861 28/27 2 1.0756905862201824742 14/13 close to 16/15 minor 2nd * 3 1.1156579177615436668 10/9 close to major 2nd (9/8) * 4 1.1571102372827198253 7/6 also close to 8/7 5 1.2001027195781030358 minor 3rd (6/5) (see how well this one fits) * 6 1.2446925894640233315 major 3rd (5/4) * 7 1.2909391979474049134 9/7 8 1.3389041012244721773 major 3rd (4/3) * 9 1.3886511426146561750 tritone (7/5) * 10 1.4402465375387590116 tritone (10/7) * 11 1.4937589616544857174 5th (3/2) * 12 1.5492596422666557249 14/9 13 1.6068224531337648149 minor 6th (8/5) * 14 1.6665240127970890861 major 6th (5/3) (see how well this one fits) * 15 1.7284437865632111533 12/7 also close to 7/4 16 1.7926641922757116385 9/5 close to minor 7th (16/9) * 17 1.8592707100168125609 13/7 close to major 7th (15/8) * 18 1.9283519958849901632 27/14 19 2 octave * *'s indicate notes that have a corresponding spot (more or less) in the 12 note octave. I found a link that talks about the history of 19 tone tunings. C G D A E B F# C# Ab Eb Bb F E.T. 1 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 16/15 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 7.71 -19.55 -41.06 -41.06 -19.55 -27.26 -11.73 9/8 0.00 -21.51 -21.51 0.00 -7.71 19.55 27.26 0.00 -21.51 -21.51 0.00 0.00 -3.91 6/5 0.00 -21.51 -21.51 0.00 0.00 0.00 -13.79 -41.06 -41.06 -48.77 0.00 0.00 -15.64 5/4 0.00 0.00 -7.71 41.06 41.06 41.06 27.26 0.00 0.00 0.00 21.51 0.00 13.69 4/3 0.00 0.00 0.00 21.51 0.00 0.00 7.71 -27.26 0.00 0.00 21.51 0.00 1.96 7/5 0.00 27.26 27.26 48.77 27.26 27.26 34.98 7.71 7.71 -13.79 7.71 7.71 17.49 3/2 0.00 0.00 -21.51 0.00 0.00 -7.71 27.26 0.00 0.00 -21.51 0.00 0.00 -1.95 8/5 0.00 0.00 -21.51 0.00 0.00 0.00 7.71 -41.06 -41.06 -41.06 -27.26 0.00 -13.69 5/3 0.00 0.00 0.00 13.79 41.06 41.06 48.77 0.00 0.00 0.00 21.51 21.51 15.64 16/9 0.00 0.00 0.00 21.51 21.51 0.00 7.71 -19.55 -27.26 0.00 21.51 21.51 3.91 15/8 0.00 -7.71 19.55 41.06 41.06 19.55 27.26 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 11.73

The piano is arguably the easiest musical instrument for kids to learn and there's a ton of easy songs to learn. It's a great way to introduce...

Read More »

Forrest clearly has an intellectual disability, but also has a physical impairment—his leg braces—as a child. Lt. Dan's missing legs are the most...

Read More »

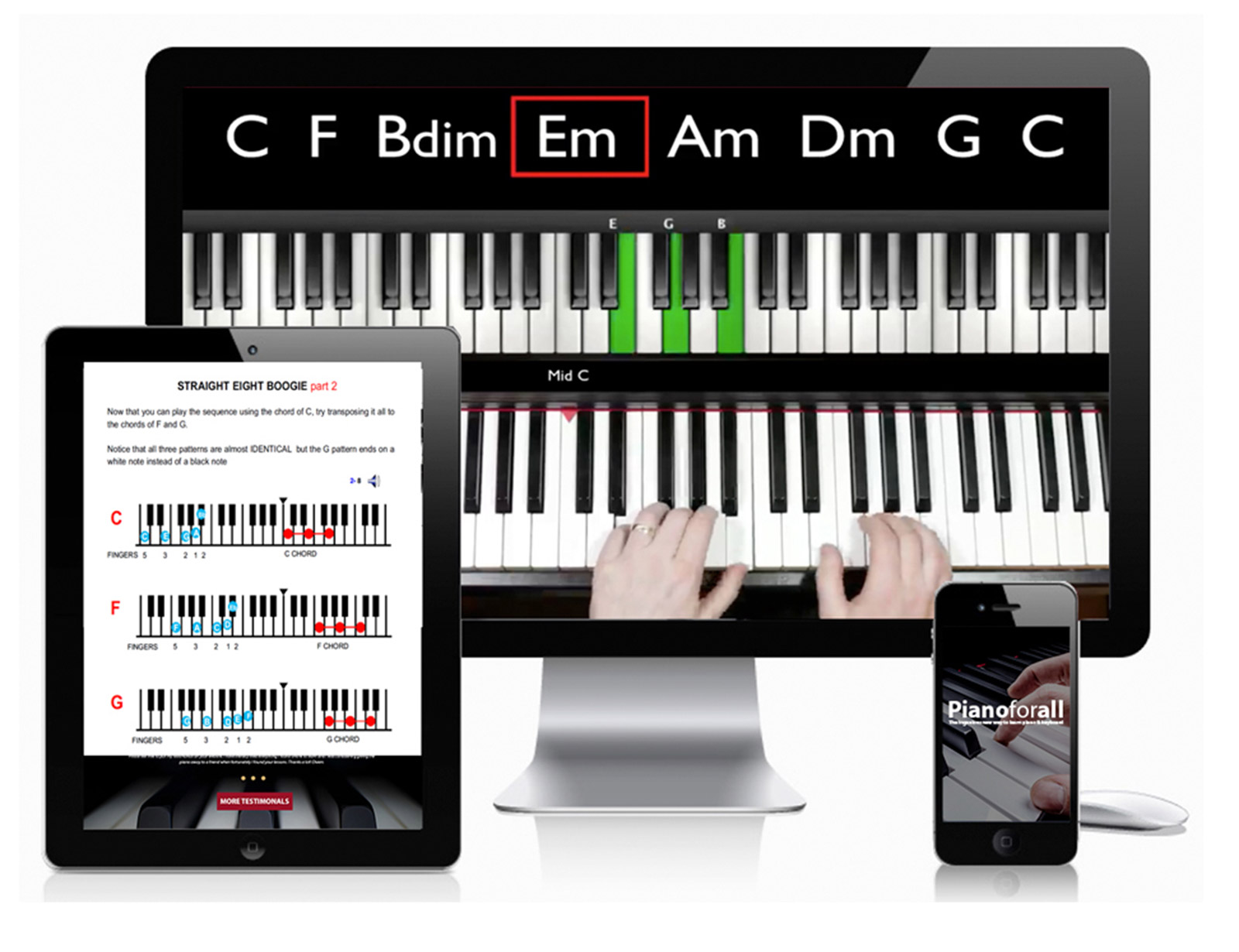

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

Driving a Manual is More Fun The last - and very best - reason to drive a stick: It's a heck of a lot more fun. Nearly every person who has owned...

Read More »

How Much Does an Upright Piano Weigh? A classic upright piano typically weighs between 500 and 800 pounds. Feb 26, 2016

Read More »