Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: Tima Miroshnichenko

Photo: Tima Miroshnichenko

These four chords are the magic I, IV, V and vi.

Ultimately, the best way to build calluses on your fingers is to play, play, play. Make sure to play every single day, even if it's just for a few...

Read More »

More Arbitrary Ratings of Proficiency Level Hours Needed Daily Practice Investment Basic 312.5 156 days Beginning 625 10 months Intermediate 1250...

Read More »

Always keep the tip of your little finger above the same string that your index finger touches. This way, you shorten the path your finger takes...

Read More »

According to Pauer, C minor is the key that is expressive of softness, longing, sadness, solemnity, dignified earnestness, and a passionate...

Read More »They can be referred to as sixth chords, but traditionally they would be called added tone chords, or, more specifically, added sixth chords. In sum, for chords arranged in thirds, the most common names are seventh-chords, ninth-chords, eleventh-chords, etc.

The name is indeed tetrad, as pointed out in a comment by Shevliaskovic. However, this term is not very common. Standard tetrads built in thirds are almost always referred to as seventh-chords. The problem is that there are two common four-part chords (yes, that's actually a very good name!) that are no seventh chords, because they contain a major sixth instead: X6, Xm6 (replace X with any root you like). They can be referred to as sixth chords, but traditionally they would be called added tone chords, or, more specifically, added sixth chords. In sum, for chords arranged in thirds, the most common names are seventh-chords, ninth-chords, eleventh-chords, etc. Chords consisting of a triad and other added tones (not in thirds) can be referred to as "added tone chords", or if you want to be more specific, as "added Xth chord", where X specifies the added scale degree (such as a sixth). For chords with more general structures I think that "N-part chord" (N=4,5,...) is the clearest and most common name. I believe that the terms "pentad" (etc.) are not at all common in music theory. There exist terms like pentachord and hexachord, but they do not necessarily refer to chords but to series of five or six notes.

Casio Privia PX-S3000 4.6 The reason being that it's the world's slimmest keyboard piano, and it still has a stunning graded hammer-action...

Read More »

String Quartet 14 Movement One The opening movement to the string quartet Beethoven considered his best is also arguably one of the saddest...

Read More »

But it's Mariah Carey who takes the prize for the largest vocal range of all. She can reach a low F2 and hit an unbelievable G7, a note that...

Read More »

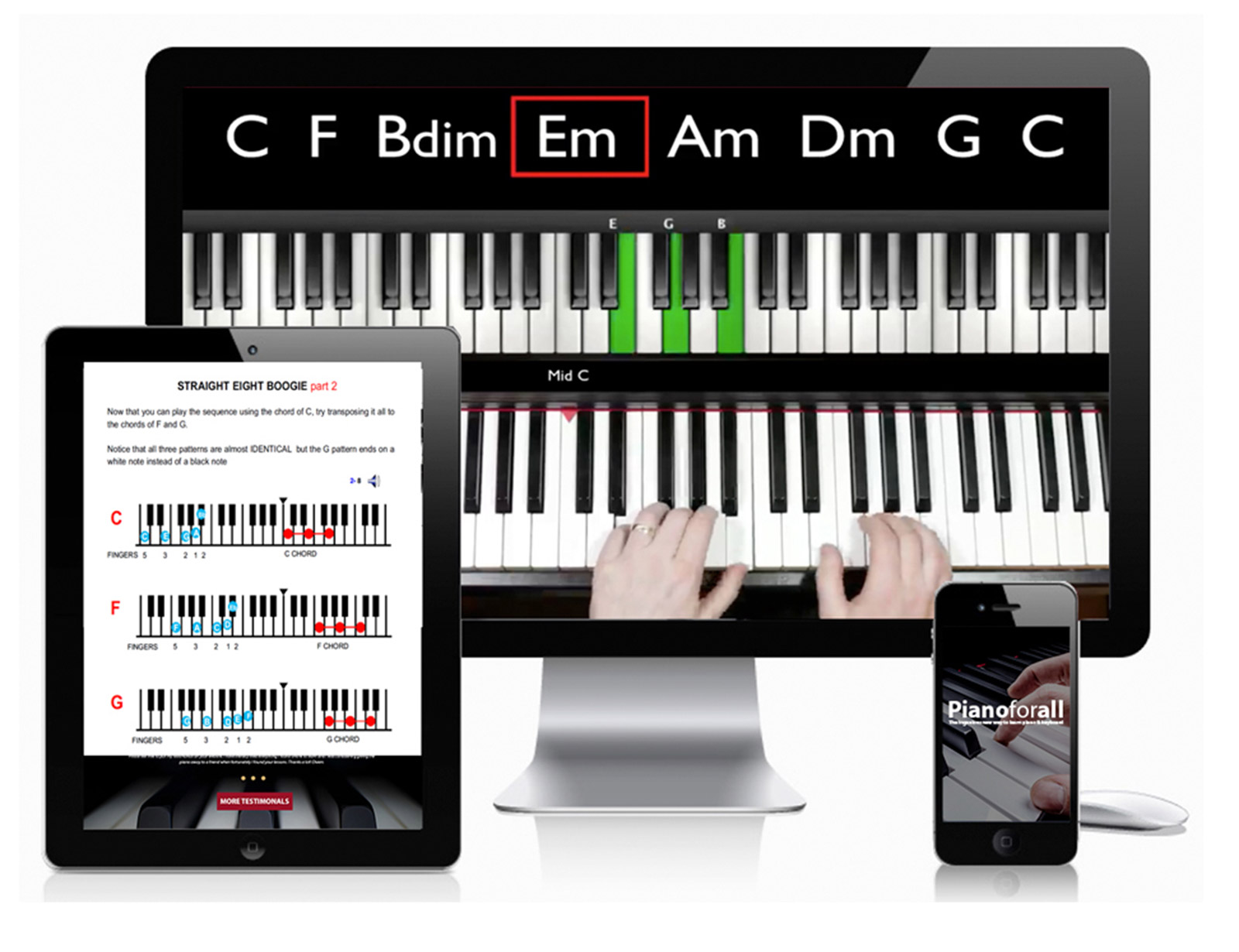

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

In fact, the digital version of Piano for All only costs $40, which is sometimes the cost of a single lesson from an experienced teacher (and...

Read More »