Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: Charles Parker

Photo: Charles Parker

Music is a field in which the word “talent” is bandied about a lot: the world is full of “talented” violinists, conductors, and rock guitarists. Obviously no one is born with the ability to play the violin; like everyone else, a talented person must learn the instrument.

nose flute Nose flute Fijian girl playing nose flute. Woodwind instrument Classification Woodwind Hornbostel–Sachs classification 421.111.12 (The...

Read More »

Kawai doesn't make as many pianos as Yamaha, but you will still find Kawai products in many places. As far as quality is concerned most would agree...

Read More »

E♭ Major Lack of Color is written in the key of E♭ Major. According to the Theorytab database, it is the 5th most popular key among Major keys and...

Read More »

There are many famous people with ADHD (aka ADD). They include athletes, actors, scientists, musicians, business leaders, authors, and artists. Jun...

Read More »The top group of musicians had gained entry to a high-level music college by taking part in a competition. These people were training to be professional musicians. We’ll call them the “A group.” The B group students were good musicians but they hadn’t done well enough in the competition to get into the college. The C group students were serious about music and had thought about applying to the college, but eventually decided against entering the competition. The D group students were learning a musical instrument for fun but weren’t considered (by themselves or anyone else) to be music college material. The E group students had started learning an instrument but had given up. It sounds pretty obvious that the A group of students, who succeeded in the competition and ended up training to be professionals, would, on average, be more talented than the B group, who would be more talented than the C group, and so on. So Professor Sloboda and his colleagues donned their computers and booted up their lab coats to look at how quickly the talented students rose through the grades compared to their less gifted compatriots. When they looked at the figures and interviewed the students and their parents, they found what they expected: the high achievers did get through their grades faster than the others. After three and a half years of training, the A group had, on average, achieved grade 3, whereas, in the same amount of time, the C group had only achieved grade 2. But when the academics looked a little closer, they began to suspect that talent was not the key to success. The numbers showed that, on average, the group A musicians needed almost exactly the same number of hours of practice as any of the other groups in order to pass the next grade exam. The average amount of practice any of the students had to put in to get from grade 1 to grade 2 was two hundred hours, no matter what group they were in. To get from grade 6 to grade 7 took on average eight hundred hours of practice. The average total amount of practice needed for any of the students to go from total beginner to achieving grade 8 was just over three thousand hours (although, of course, they didn’t all go that far). The conclusion was simple: the more you practice, the faster you become a good musician. The only “gift” the A group students had was the gift of diligence: they started off practicing more than the other groups and also increased the amount they practiced as the years progressed. This group started off doing about half an hour’s practice a day in their first year of learning their instrument, and increased to over an hour a day by their fourth year. The lower-achieving students started off doing less than half an hour and didn’t increase the amount of practice time much in subsequent years. (For example, group D started at only fifteen minutes a day and rose to the dizzying heights of twenty minutes over those initial four years.) On average, group A students weren’t especially talented; they just put in more hours of work every week. The results of the Sloboda study were confirmed by another group of psychologists, who carried out a study of music students in Berlin in the early 1990s. The researchers began the project by asking the staff of the Music Academy of West Berlin to rank their violin students into three groups — let’s call them excellent, good, and ordinary. The researchers then analyzed how all the students spent their time on an hour-by-hour basis and also looked into the history of their musical training. They found that the students were very similar in many ways. They had all started their training at about the age of eight, and they all spent about fifty hours a week involved in various musical activities. The only big difference between the groups was how much solo practice they did. The excellent students had, on average, 7,410 hours of solo practice under their belts by the time they were eighteen years old, compared to 5,301 hours for the good students and only 3,420 hours for the ordinary ones. These figures fit in well with the generally accepted rule that just about anybody can achieve a professional standard in nearly any skilled activity — from athletics to zoology — if they put about 10,000 hours of prac- tice into it (and in case you’re wondering, 10,000 hours is equivalent to about four hours a day, every day, for seven years).

Franciszek Honiok (1896 – 31 August 1939) was a Polish man who is famous for having been the first victim of World War II, on the evening of 31...

Read More »

You are never too old and it is never too late to start learning the violin. While learning the violin can be a lot of fun at any age, there are...

Read More »For those of you who were keen on the concept of talent and resent the idea that musical achievement can largely be attributed to simple, boring hard work, please don’t forget, this makes the high achievers more admirable — not less. When parents proudly describe the musical talent and potential of their beloved offspring, they are, without realizing it, actually talking about how well the child has already progressed on the instrument in question. They don’t point at little Henry before he’s laid his sticky fingers on a violin and say, “He looks like he would be a marvelous violinist.” They actually wait until the child has acquired some skills and then declare his genius for playing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” or “Smoke on the Water.” They seem to have forgotten the weeks of squeaks and all the hard work involved. The key to acquiring high-level musical skills is something called deliberate practice. The more deliberate practice you do, the better you get — and this applies to any skillful activity. But deliberate practice is not the same thing as ordinary practice. Ordinary practice often involves simply repeating something you can already do pretty well. Deliberate practice, by contrast, means that you are taking a step forward. You are doing something you find difficult — and once you have mastered it, you will be a step nearer to perfecting your skill. One of the defining characteristics of deliberate practice is that generally it isn’t fun—which is why excellence is rare. The film producer Sam Goldwyn once famously said, “The harder I work, the luckier I get,” and for musicians this could be reworded as “The harder I work, the more talented I get.”

D minor Composition and lyrics In terms of music notation, the song is composed in the key of D minor, with a tempo of 147 beats per minute, and...

Read More »

Yes, digital pianos require servicing; just not as much as classic, wooden ones. This is because, contrary to what most people think, digital...

Read More »

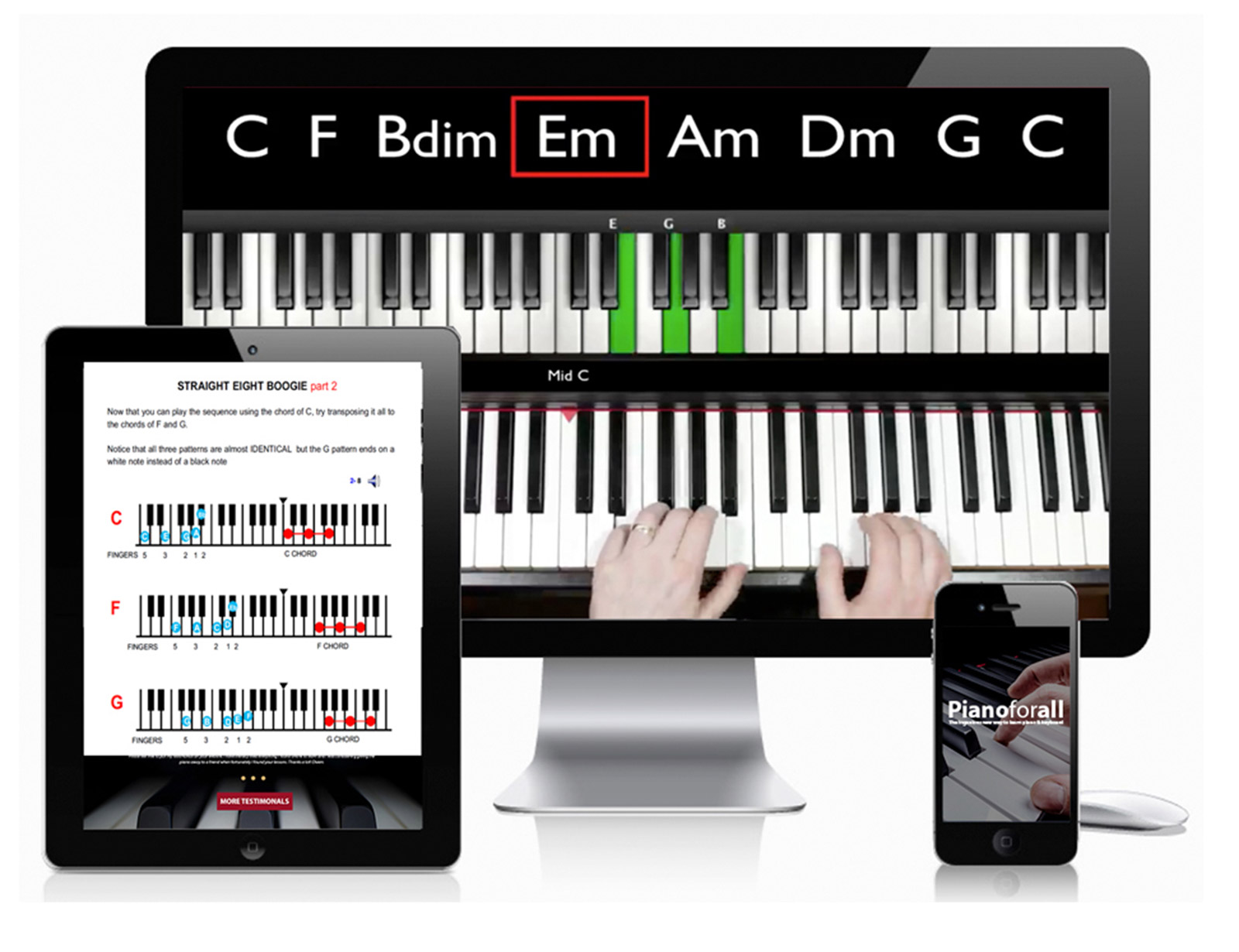

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

As It Was is written in the key of A Major. According to the Theorytab database, it is the 4th most popular key among Major keys and the 4th most...

Read More »

There are 12 unique notes at the piano, which means we can build a major chord on each of those 12 notes - C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, Ab, A, Bb, an...

Read More »