Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

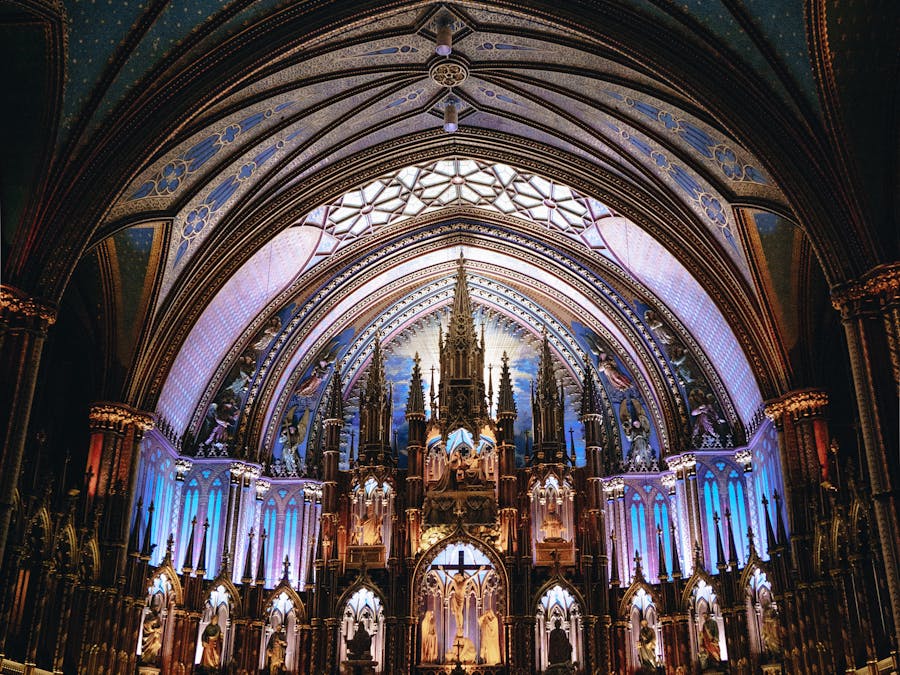

Photo: Julia Barrantes

Photo: Julia Barrantes

homophonic Mostly homophonic. Consists of two themes, the first more lyrical; the second more march-like.

The number 77 is often seen as a sign of good luck, protection, and spiritual guidance. Apr 13, 2022

Read More »

Ephesians 5:19 says, “singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart.” It is to him and about him that we sing! Singing has such a unique...

Read More »

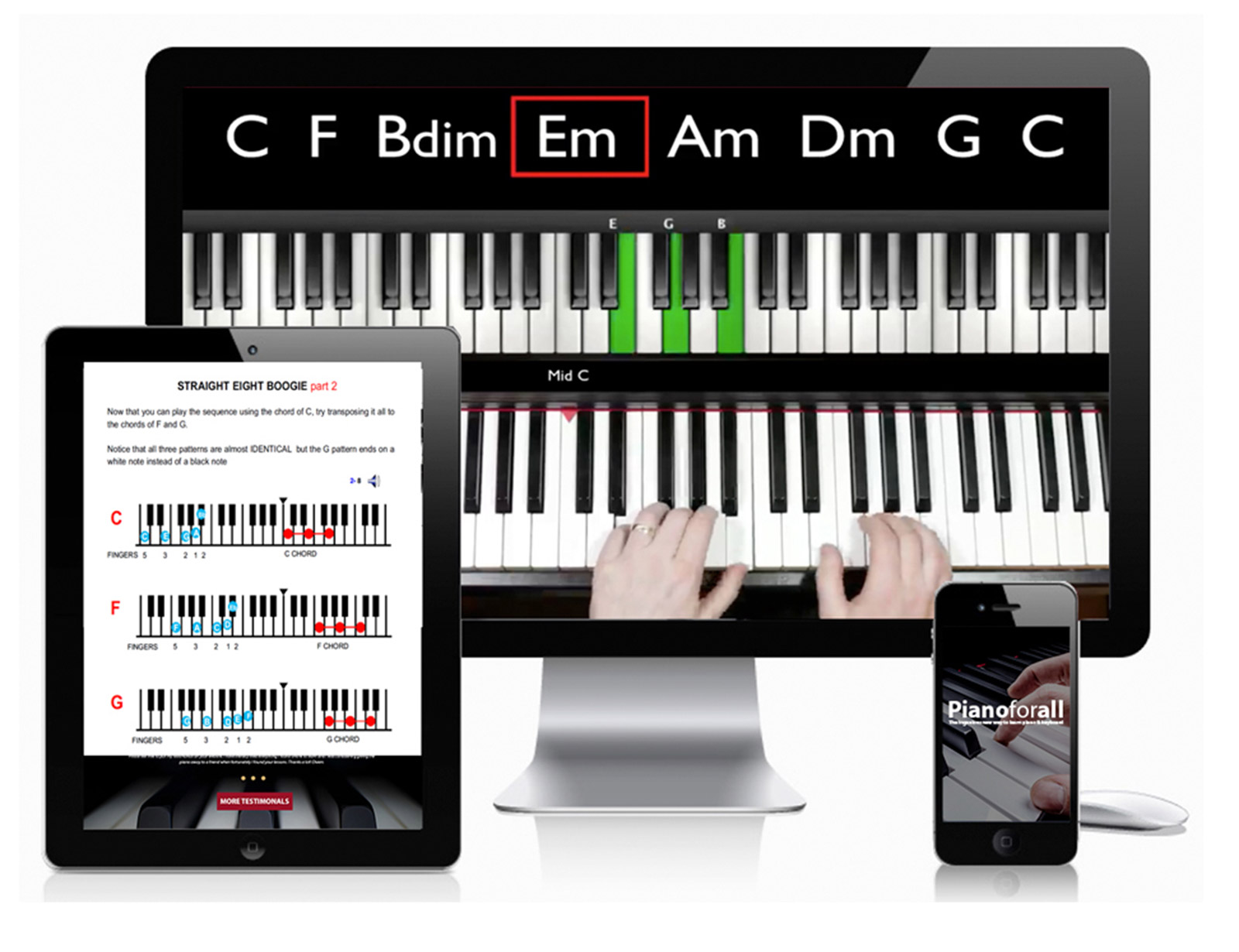

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »Beethoven was born in Bonn in December of 1770. As you can see from the map at the beginning of this chapter, Bonn sat at the Western edge of the German- ic lands, on the Rhine River. Those in Bonn were well-acquainted with traditions of the Netherlands and of the French; they would be some of the first to hear of the revolutionary ideas coming out of France in the 1780s. The area was ruled by the Elector of Cologne. As the Kapellmeister for the Elector, Beethoven’s grandfather held the most important musical position in Bonn; he died when Beethoven was three years old. Beethoven’s father, Johann Beethoven, sang in the Electoral Chapel his entire life. While he may have provided his son with music lessons at an early stage of Ludwig’s life, it appears that Johann had given into alcoholism and depression, especially after the death of Maria Magdalena Keverich (Johann’s wife and Ludwig’s mother) in 1787. Although hundreds of miles east of Vienna, the Electorate of Cologne was un- der the jurisdiction of the Austrian Habsburg empire that was ruled from this Eastern European city. The close ties between these lands made it convenient for the Elector, with the support of the music-loving Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein (1762-1823), to send Beethoven to Vienna to further his music training. Ferdinand was the youngest of an aristocratic family in Bonn. He greatly support- ed the arts and became a patron of Beethoven. Beethoven’s first stay in Vienna in 1787 was interrupted by the death of his mother. In 1792, he returned to Vienna for good. Perhaps the most universally-known fact of Beethoven’s life is that he went deaf. You can read entire books on the topic; for our present purposes, the timing of his hearing loss is most important. It was at the end of the 1790s that Beethoven first recognized that he was losing his hearing. By 1801, he was writing about it to his most trusted friends. It is clear that the loss of his hearing was an existential crisis for Beethoven. During the fall of 1802, he composed a letter to his brothers that included his last will and testament, a document that we’ve come to know as the “Heiligenstadt Testament” named after the small town of Heiligenstadt, north of the Viennese city center, where he was staying.

It was first performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824. The symphony is regarded by many critics and musicologists as Beethoven's greatest work and one of...

Read More »

Most keyboards come with 66, 72, or 88 keys. For a beginner, 66 keys are sufficient for learning to play, and you can play most music on a 72-key...

Read More »

How Often Should You Script to Manifest? If you're new to scripting, you should script daily for at least 40 days. It takes around 40 days for you...

Read More »

The test consists of heating up the point of a needle until it's red-hot and then pricking what you believe is your ivory carving. If the needle...

Read More »The staccato first theme comprised of sequencing of the short-short- short-long motive (SSSL) greatly contrasts the more lyrical and legato second theme

This word sonata originally meant simply a piece of music. It comes from the Latin word sonare, to sound; so a sonata is anything that is sounded...

Read More »

Practice Tips Practice everything – scales, licks, voicings, improvisation and songs – in every key, especially your weak keys. Accuracy is more...

Read More »

So, why does a piano have to be on an inside wall? An inside wall helps protect the piano from direct sunlight and sudden changes in temperature....

Read More »

According to Education Next, teachers retire, on average, at around the age of 58. AARP reports that 33 percent of all beginning teachers leave the...

Read More »