Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: Vasiliy Skuratov

Photo: Vasiliy Skuratov

“There is no such thing as perfect sound,” he says. “But how do you explain what this sound is?

Align the text to the left. Ctrl+L. Align the text to the right. Ctrl+R. Cancel a command.

Read More »

The Home Depot makes house and office key copies for major brands such as Schlage and Yale. Older or rare keys may be copied if a suitable blank is...

Read More »

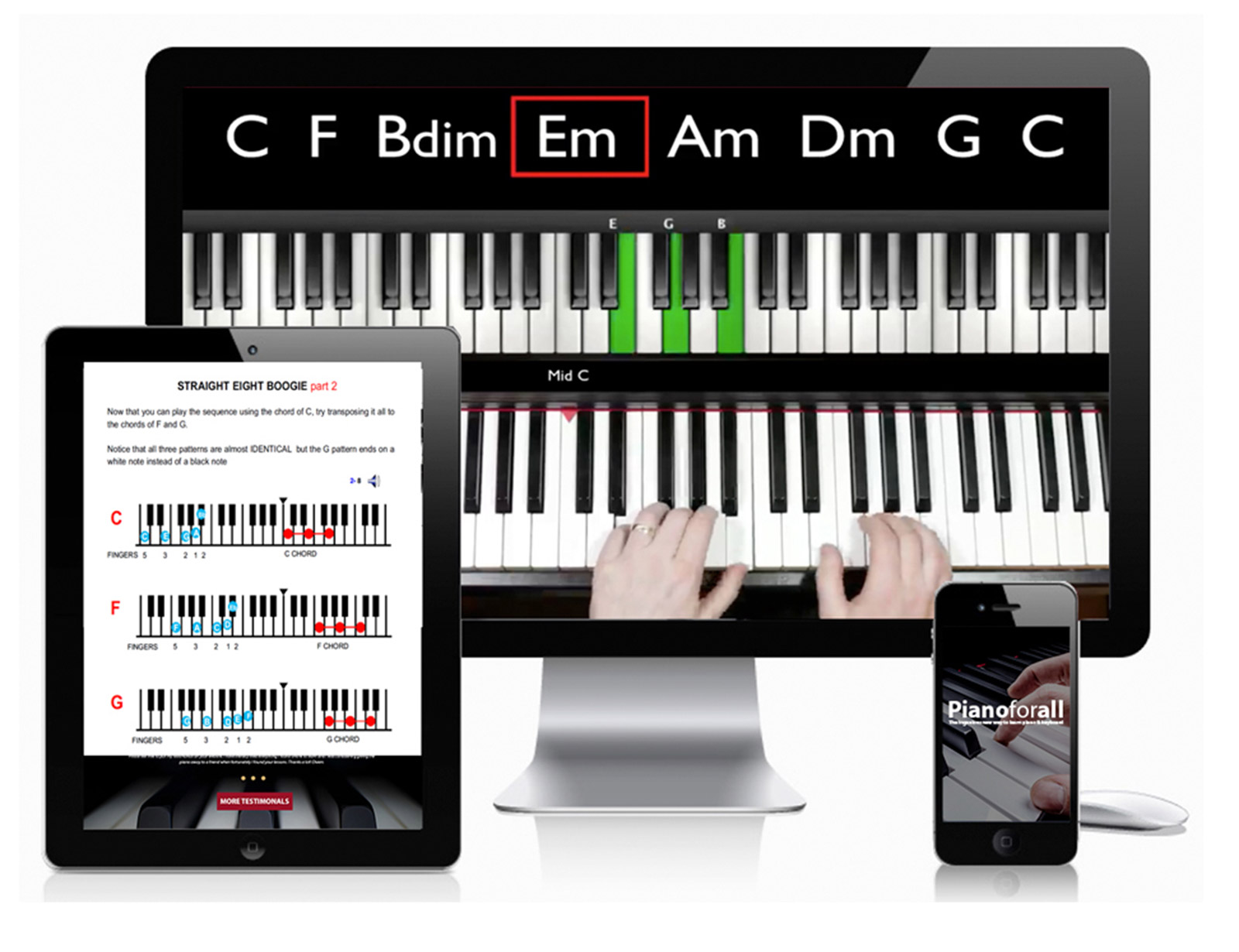

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

That's right: 49 keys are enough to get started. Because your instrument is really made up of repeating sets of 12 notes, as long as you have a few...

Read More »

Women love creative people and if its a man, then it is just perfect. Playing the guitar is a whole different level of creativity that attracts...

Read More »Track 3 1 2 4 5 6 Goodbye iPod, hello streaming Early this year, Apple ended the iPod era after 21 years and 450 million sold. The death of the digital music player inspired several nostalgic articles, but for me and most others, it had been so long since I’d used my last iPod. By now, I was well into streaming and, specifically, trying to experience high-resolution audio. As I explored, I needed a way to listen to those high-res files. The iPhone’s space-saving sound chip wouldn’t work. I needed a digital-to-analog converter, or DAC, I could plug into my system. These machines take the math exercise that is a digital signal and turn it into the continuous wave that is analog. Tony Stott, the head of product marketing for the London-based Cambridge Audio, suggested I pick up a CXN V2 DAC (retail $1,299). Then I told him about the larger quest I was on. And how I’d been mocked by Port and some of the other audio guys. They said my search was hopeless, that my system could never sound good enough because I wasn’t willing to clear out enough space for suitably sized speakers. “What can sometimes happen is that some of the joy of the music is overtaken by the joy of building a system,” Stott said. “But listening to good-quality audio is a bit like owning a Formula One team. It will cost you a million pounds to get around the track in two minutes. It will cost you 10 million pounds to get around the track in a second under two minutes.” Stott also cautioned me that it wasn’t enough to get a DAC. I also needed to consider the source. “Rubbish in, rubbish out,” he said. “Not to say that Spotify is rubbish, it has its place, is brilliantly convenient and it’s wonderful for on-the-go in the car, but when you start taking a high-resolution file and feed it into a good digital-to-analog converter, there’s a big lift.” For me, that lift would be Qobuz, a digital music service founded in France in 2007 and still a very small fraction the size to Spotify. “In the U.S., we have seven people. Not seven people at the front desk,” says managing director Dan Mackta of his workforce. “Seven people.” Mackta won’t tell you how many people subscribe to Qobuz. (That number is also but a very small fraction of Spotify’s users.) But for almost a year, I’ve been one of them. There are limitations — no podcasts, for example — which is why I pay $12.99 a month for Qobuz but still subscribe to Spotify. You don’t need to understand bit rates to get why I’m paying for both services. Just put on the same track — say, the Rolling Stones’ apocalyptic anthem “Gimme Shelter” — on Qobuz and Spotify and you’ll hear a clear difference. Now how sharp are your ears when it comes to low- and high-resolution digital audio? Can you tell which sample below is higher quality? 2 Don’t forget to plug those wired headphones in if they aren’t already. 2These two versions of “I Feel The Earth Move” are digital files, one a lower quality (16bit_22kHz) MP3 file heard in the earlier days of file sharing, the other a high-resolution (24bit_96kHz) .WAV file from Qobuz. Note that a Bluetooth connection may not support high-resolution streaming. Carole King — “I Feel The Earth Move” Sample one Sample two Which sample is the high-resolution file? It's definitely sample one. Pretty sure it's sample two. For all its limitations, digital is mostly a known quantity. If you listen to enough new records, you’ll realize why Tom Port’s business is thriving. Old records in excellent condition can cost hundreds. New pressings are miss as much as hit. Some of them are warm and dynamic, others are dull and muddy. There’s no way to know what you’re getting until you throw down $40, rip open the plastic and put that new disc on your turntable. Why does a Hank Mobley reissue mastered by Kevin Gray sound so good when a Chet Baker reissue by the same engineer falls flat? “That’s one of the big problems with vinyl,” says Bernie Grundman, the 78-year-old mastering engineer whose lengthy career has included working on Carole King’s “Tapestry,” Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” and Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic” and who now oversees a company booming with reissue jobs. “When we started getting back into vinyl in a big way, I said, ‘Okay, now we’re ready for a lot of headaches.’ ” Sometimes, the record company won’t deliver the original master tape and he’s stuck with a digital file (the 25th anniversary reissue of the “Buena Vista Social Club”). Sometimes the original tape is damaged (Sonny Rollins’s “Newk’s Time”) and he has to tirelessly patch together sections from old CDs. Then there are the production chain woes. A great record is always going to sound better than its digital counterpart, but, Grundman says, “to get a really great record is next to impossible.” A framed “Thriller” record with a note signed by Michael Jackson on a wall of records that American audio engineer Bernie Grundman has worked on over the years. (Damon Casarez for The Washington Post) American audio engineer Bernie Grundman photographed in his mastering studio. (Damon Casarez for The Washington Post) LEFT: A framed “Thriller” record with a note signed by Michael Jackson on a wall of records that American audio engineer Bernie Grundman has worked on over the years. RIGHT: American audio engineer Bernie Grundman photographed in his mastering studio. (Damon Casarez for The Washington Post) Track 4 1 2 3 5 6 Massive demand, limited supply It’s 4:50 a.m. in Taipei, Taiwan, and Danny Lin is waking up to the sound 0f his iPhone alarm. He is 49 and the vice president of an internet browser company, and he lives with his wife and two children in a condo. He also really wants a copy of Yusef Lateef’s “Eastern Sounds.” An original copy of the saxophonist’s 1961 album will cost hundreds. But Craft Recordings is putting out a special reissue for $100 as part of its “small batch” series. Grundman has mastered this reissue, and it’s also a “one-step,” meaning parts of the production process usually used in the making of a record are eliminated. This is supposed to make the Craft record sound closer than ever to the original session tapes. 4:58. 4:59. 5 a.m. Click. Lin places the record in his cart and enters his credit card information, but poof, the album is no longer there when he tries to finalize the transaction. Sold out. He tries again, with no luck. All 1,000 copies are already gone. Or rather, they’re just available somewhere else now. He checks eBay where he already sees multiple listings for the Lateef record on the auction site, most in the $500 range. Another victory for the flippers. “That price is crazy,” says Lin. “I’m never going to trust Craft again.” I know how he feels. Because there is at least one other person who has clicked through and struck out the same way. Me. This is a long way from the ’80s, when I could gobble up used copies of Howlin’ Wolf or the Pretenders for $8. But then, as CDs grew more popular, the record industry morphed. Pressing machines were destroyed, record plants converted. The only problem is that records didn’t die. They just went into hibernation. And then, when they came back, the infrastructure that enabled record companies to press as many as 350 million records a year during the “Hotel California” era was gone. “I think about it all the time,” says Josh Bizar, vice president of Music Direct. “How did Led Zeppelin make 4 million copies to introduce their albums to the world when we have trouble making 5,000 of anything?” The “Eastern Sounds” reissue followed the familiar game plan in this new soundscape. Put out something old and special. Package it in a beautiful box. And promise, through a technical explanation that’s beyond the understanding of most civilians, that this album is “as close as the listener can get to the original recording.” Then sit back. Craft, for its part, says it made an honest mistake in one part of the process and by the time its next release came out, a reissue of Miles Davis’s “Relaxin’,” pressings were increased from 1,000 to 5,000 copies. “We really didn’t anticipate it to sell out as quickly as it did,” says Mark Piro, who is a director of artists and repertoire for Craft Recordings, the catalogue division of Concord. “We don’t want people to be left out. That’s not our goal.” The vinyl boom can be charted pretty easily. In 2008, Radiohead had the No. 1 record on the vinyl charts. “In Rainbows” sold 25,000 copies. That wouldn’t even land in the top 100 of 2021. Just last year, new albums from Adele, Olivia Rodrigo and Taylor Swift sold more than 250,000 vinyl copies each. Then there’s the thriving market of reissues, which range from the slew of sealed records pumped out by major labels to the more particular releases aimed at audiophiles from companies such as Analogue Productions and Intervention Records. Everybody faces the same challenge. Massive demand, limited supply. “Physics dictate how many records you can make,” says Billy Fields, who leads commercial vinyl strategy at the Warner Music Group. “It takes basically half a minute to make a record. And then you just back out from there. How many presses do you have working? How many shifts are those presses operating? How efficient are those presses? How many records basically is every press putting out every single day that it’s in operation? And what’s the grand total of that?” He actually has a number: 170 million records. That’s how many Fields says can be pressed in the world each year. To keep up with demand, the industry would need to produce 350 million. That accounts for indie releases, Beatles and Stones reissues, the latest from Harry Styles. They are for audiophiles with $20,000 turntables in special listening rooms and kids with portable Crosleys. All of a sudden, these records are for everyone. A turntable at Brittany's Record Shop in Cleveland on Record Store Day, April 23. (Amber N. Ford for The Washington Post) Track 5 1 2 3 4 6 Happy Record Store Day! It wasn’t easy to find Brittany Benton. There are no signs for her pop-up record store, a space found in an industrial building in St. Clair Superior, an east Cleveland neighborhood that’s peppered with vacant homes. I drove around the building twice, parked in a dusty lot and stopped somebody walking to her car with an Ari Lennox record under her arm. Elise Burnett Boyd pointed me down the lot to Dock 5, to a door propped open with a cinder block. “Just follow the music,” she said. I could hear the groove of Hall and Oates’s “I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do)” and, at the end of a hallway, spotted Benton, 35, wearing a brown hoodie and sitting against the wall as she priced out records. Owner of Brittany’s Record Shop, Brittany Benton, chats with customers between purchases on April 23. (Amber N. Ford for The Washington Post) Benton sold records online through the pandemic, but these days, she’s renting a 25-by-25 section of floor in this 120-year-old factory building for $300 a month. I’m coming to see her because she’s not obsessed with rare pressings and $100 reissues. She’s just selling records. It also happens to be Record Store Day, which was created in 2007 to gin up excitement around vinyl but has morphed into a flipper’s dream, with dozens of limited editions produced just for this event. Signs or no, by 11 a.m. Benton has had enough business already to earn back her rent. She’s also filled the space with sound. She has a DJ on-site and talks about abiding by the guidelines of the now 14-year-old vinyl holiday. She knows she could make more by putting the limited-edition RSD albums on eBay. She also knows that would be bad form. “It’s not a record store’s right to be in Record Store Day so much as it’s a privilege,” Benton says. “And if we’re taking part, it’s almost like a pledge that we will respect things. I’m not going to take an album that didn’t sell well and sell it on eBay the next day for 10 times the price. That discourages the everyday person coming in who wants to have access to these records. I’m not trying to hawk or shark records.” She’s trying to build a community. Tony Tanori, a 50-year-old bank analyst who had all but abandoned records during the CD era, picks up a stack. He got back into records after a friend told him about a vinyl club that meets once a week at the Winchester Music Tavern in nearby Lakewood, Ohio. He might bring his Bone Thugs-N-Harmony. Another guy might throw the Stanley Brothers on the table. “There is nothing like putting a needle to a vinyl record,” he says. A DJ plays some tunes for customers to enjoy as they are in Brittany’s Record Shop. (Amber N. Ford for The Washington Post) Cleveland locals search crates and racks, looking for records to add to their collections at Brittany’s Record Shop on Record Store Day. (Amber N. Ford for The Washington Post) LEFT: A DJ plays some tunes for customers to enjoy as they are in Brittany’s Record Shop. RIGHT: Cleveland locals search crates and racks, looking for records to add to their collections at Brittany’s Record Shop on Record Store Day. (Amber N. Ford for The Washington Post)

The septet's name, BTS, stands for the Korean phrase Bangtan Sonyeondan (Korean: 방탄소년단; Hanja: 防彈少年團), which translates literally to "Bulletproof...

Read More »

Digital pianos and keyboards can be out of tune relative to 440 Hz. This can be rectified in two ways: transposing in small increments back to 440...

Read More »Track 6 1 2 3 4 5 Lessons from the last year Over the last year, I’ve learned a lot. I’ve also spent a lot. I replaced my 1970s-era Pioneer SX-737 receiver with a vintage McIntosh 1900 and then sold that to buy a tube amplifier built by Rogue Audio. I turned a restored Thorens TD 125 — and about $2,500 — into a Technics SP-10. I gave my son my Bose speakers and tried Harbeths and then settled on Focal Aria 906s. I’d never invested so much in a stereo, and it sounded excellent to me. Still, when I referenced virtually any element of it to my audiophile sources, they made it clear I had not gone far enough. Which made me think of something I heard from Andy Zax, the music historian and producer. We are, he wrote during an email exchange, prisoners of our own expectations. So focused on FOMO and equipment and who says what on which message board that we lose sight of the most important question: How do we have an enjoyable listening experience? Which brings me back almost to where I started: Michael Fremer. Things had not gone well between us. For almost a year, the pioneering audiophile writer and I had gotten along swimmingly as we chatted about gear and recordings. He had generously offered me insight and sources. Then I wrote about the MoFi scandal and Mike Esposito, which infuriated Fremer. Those two had been feuding online for months, and the MoFi situation only exacerbated their conflict. Fremer slammed Esposito for spreading a rumor before he could confirm it and then, after the rumor proved correct and the record store owner went to MoFi’s headquarters to talk with the company’s engineers, Fremer took to YouTube to criticize his interviewing skills, calling him a “fanboy” who got “rolled over.” After my MoFi story published, Fremer was furious with me. He peppered me with angry text messages, made a 10-minute YouTube video retort to my piece and called me a liar online. Fremer, who is 75, has a long history with music, dating back to his time during the 1970s at WBCN, the powerful Boston radio station. He worked as music supervisor of the movie “Tron,” in 1982 and shortly after, focused on writing about audio and specifically fighting for the superiority of vinyl as a format. He was a crucial component of this story, but he wanted nothing to do with me. “He was one of the only ones waving the analog flag in the cold, sterile digital day,” Chad Kassem told me. “I’ll work on him.” The next day, a text arrived. “The only way to move forward is for you to do what I’ve been asking you to do for it seems like years: visit and spend most of a day listening to records here,” Fremer wrote. Michael Fremer, the pioneering audio writer, after attending a listening party in June hosted by Christie's to hear Bob Dylan’s new recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind” before it headed to auction. (Jackie Molloy for the Washington Post) So on a Thursday in August, I drove four hours from Boston to the white Colonial Fremer shares with his wife, Sharon, just outside of Newark. Fremer warmly shook my hand and ushered me downstairs. “This is not an audio salon,” he said as we got settled. “This is a workspace.” The basement is cramped, packed with records and Fremer’s equipment, which includes Wilson XVX speakers (retail: $329,000) and the turntable he has decided will be his last, a prototype of Weiss’s K3. I realized quickly that Fremer wasn’t going to mention our conflict. He sat me in a comfortable chair in the center of the room as he pulled out the British pressing of “Rubber Soul” that he bought when he was 19. It’s hard not to be impressed by the harmonies, Ringo’s snare and Paul’s snaky bass when you’re in front of those $300,000 Wilsons. We listened to an Electric Recording Co. issue of Thelonious Monk’s “Brilliant Corners.” Fremer offered high praise for Hutchison’s work. He also showed me how many inconsistencies this system could expose. He played “In My Room” off a 2015 reissue by Analogue Productions to slam a version released earlier this year by Capitol Records. “This is an inept mix,” he said of the newer release. “Like mush on the bottom and then there’s that horrible ssss on top.” Story continues below advertisement Story continues below advertisement Advertisement Story continues below advertisement Story continues below advertisement Advertisement Fremer wanted to focus on MoFi records to show me what he considered the label’s bad sound formula. I wanted to know what it was about my article that upset him so much. What bothered him most, he said, was that I wrote that MoFi’s secret would not have been revealed without Esposito. “It would have taken longer, but I was on the case,” Fremer said. “I would have gotten to the bottom of it. That’s what I do.” Whatever his approach and temperament, when you sit with Fremer listening to music, it’s clear what drives him. He wants to sit in a room as you listen to his favorites — an acetate of the Who’s “Tommy,” a Weavers performance, the British pressing of Elvis Costello’s “Imperial Bedroom” — and luxuriate in the sonic beauty. “Do you think there is a perfect sound?” I asked as he searched through a pile of records. He shook his head. “There are some incredibly great records,” he said. “Great recordings. Perfect? I don’t know what that means, even.” I reminded him of when we met for the first time. In June, T Bone Burnett threw a listening party in New York City for that special, one-of-a-kind Bob Dylan rerecording of “Blowin’ in the Wind” he was auctioning. I had wondered if there, in that studio, we might find that perfect sound. An idea that Burnett quickly dismissed. That got Fremer excited. He jumped into the stacks and pulled out a Japanese pressing of a record of the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. It features Dylan doing the same song with backing from Joan Baez, the Freedom Singers, Pete Seeger and Peter, Paul and Mary. “Just sit back and relax,” Fremer told me. “Close your eyes, and let the space envelop you.” Two microphones captured that live performance. The lone instrument was Dylan’s acoustic guitar. The record wasn’t cut at half-speed or on clarity vinyl. It wasn’t part of a limited reissue released at midnight. It was an ordinary record in every way except for what came out of the speakers. You could close your eyes, hear Baez’s voice rising behind Dylan, and have something, perfect or imperfect, you wanted to hear again and again. Audio equipment in Bernie Grundman’s mastering studio. (Damon Casarez for The Washington Post) correction A previous version of this story said Music Direct was the parent company of Mobile Fidelity. They have the same owner. The story has been corrected.

In the Grade 1 examination, candidates need to know how to play scales in C, G, D and F majors as well as A and D minors. They can play each hand...

Read More »

In 1877, the ruling British government banned the drums in an effort to suppress the prominent African culture. Bamboo tubes, called tamboo bamboo,...

Read More »

The consensus is that guitar is an easier instrument to learn than violin, and that it takes more practice time to get to a performance-worthy...

Read More »

Seven Easy Piano Songs for Beginners Twinkle Twinkle. Twinkle Twinkle Little Star is always popular, especially with young students, but adults who...

Read More »