Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: FUTURE KIIID

Photo: FUTURE KIIID

The greatest threat, by far to elephants today however, is poaching (illegal killing), spurred by the global demand for ivory. Unlike deer that shed and regrow their antlers yearly, elephants do not shed their tusks; they must be killed (or severely injured) to harvest their ivory.

C minor The compositions of Ludwig van Beethoven in the key of C minor carry special significance for many listeners. His works in this key have...

Read More »

Pianists usually sit at the edge of the piano bench to allow their legs to comfortably use the pedals. Sitting at the edge of the piano bench...

Read More »

What actually happens is that the calming effect induced by classical music releases dopamine to spike pleasure. The dopamine also prevents the...

Read More »

In-ears block out the sound of the amplified instruments and acoustic instruments like drums, allowing you to have the mix at a lower level and...

Read More »

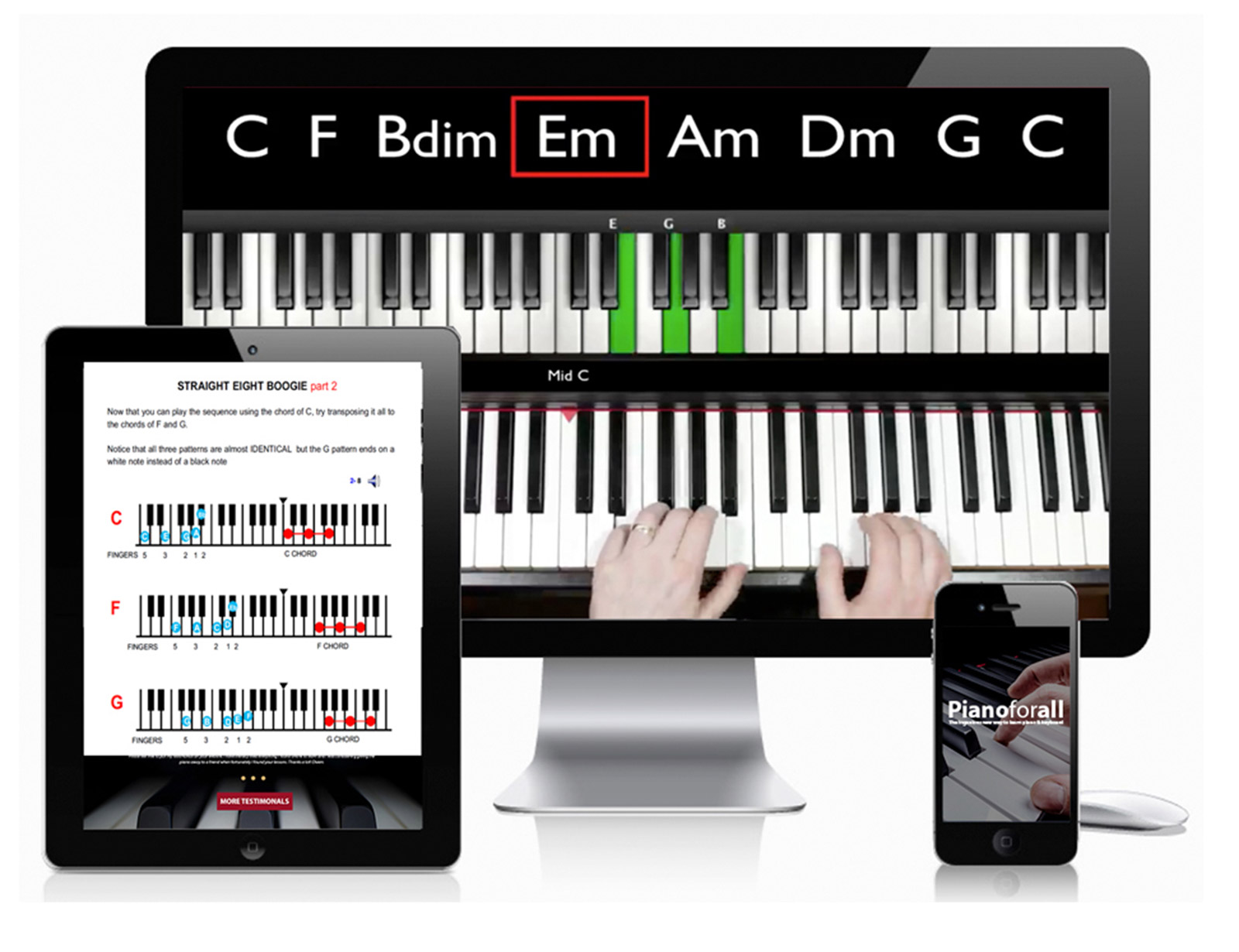

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

How Often Should A Piano Be Restrung? A general rule of thumb is that all of the strings in a piano should be replaced every thirty years. This is...

Read More »

So, can you learn piano on 61 keys? Yes, you can learn how to play the piano on 61 keys, but there will be limitations on what music you can play....

Read More »Vegetable ivory is composed of cellulose, or plant material, and can only be used to produce relatively small artifacts due to the size of the nuts.

A study suggests that minor and major seventh chords are the happiest sounds in music, but today's songwriters are ditching them in favour of...

Read More »

For example, New York, New Jersey, Hawaii, and California have banned any sales of mammoth ivory. Jul 1, 2018

Read More »

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »

13 is a great age to begin learning piano. And since you're just starting and are still plenty young, be open to other avenues for the skill. Maybe...

Read More »

1956 1956-Steinway along with the other American piano manufacturers all agreed to abandon ivory and start using plastic for keys.

Read More »