Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Piano Guidance

Photo: cottonbro studio

Photo: cottonbro studio

So pianists' brains actually are different. They are masters of creative, purposeful and efficient communication because of the very instrument that they play. They are the naturally efficient multi-taskers of the musical world, because when you're a player like Yuja Wang, there is zero room for doubt and hesitation.

Top 10 Instruments for Children to Learn to Play Music The Xylophone. Hand Percussion. Piano. Ukulele. Drums. Recorder. Violin. Guitar. More...

Read More »

Threshold of reliably playable used uprights: $1,001–$3,000 Within this range, a recent and more lightly-used upright is possible in a fair to good...

Read More »

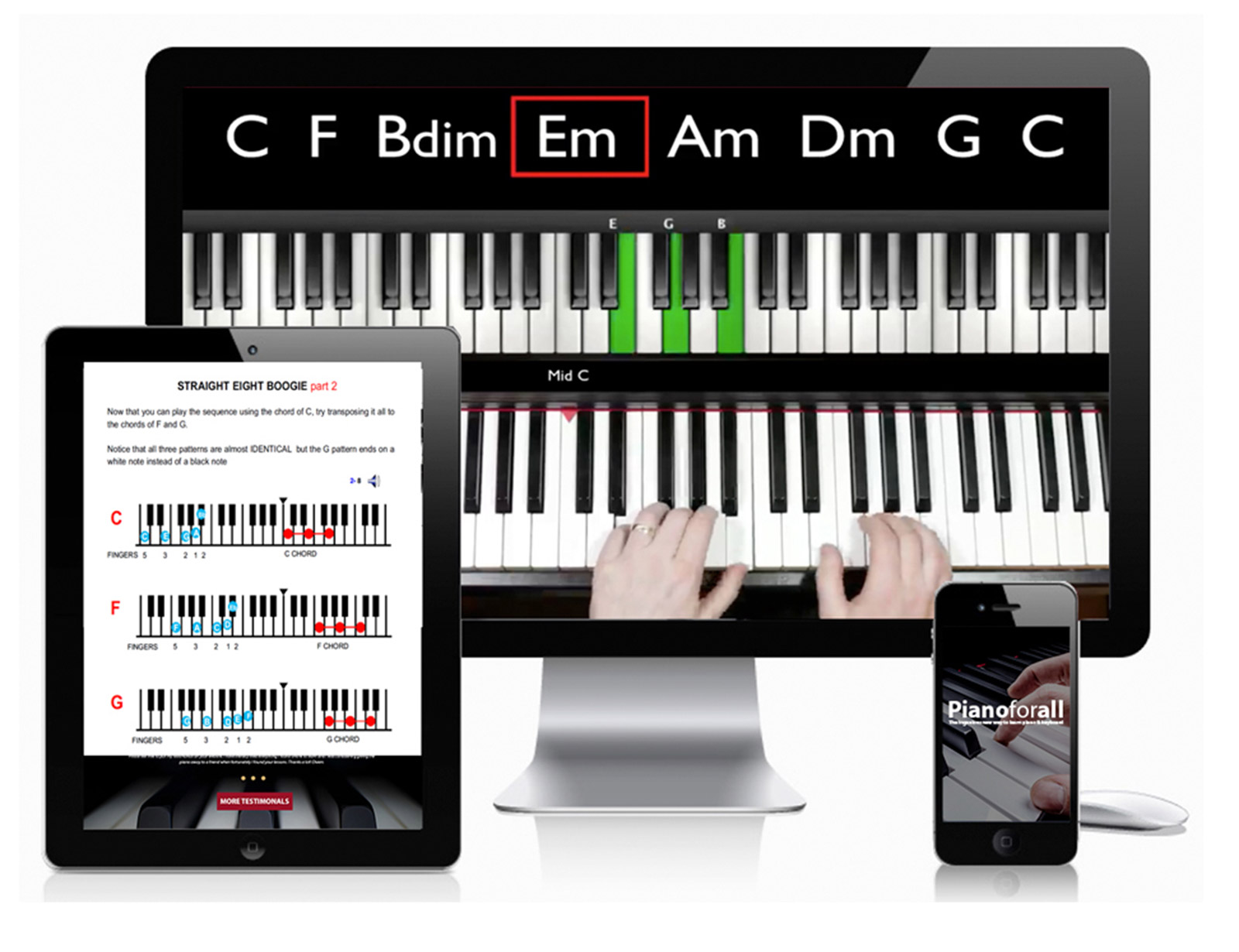

Pianoforall is one of the most popular online piano courses online and has helped over 450,000 students around the world achieve their dream of playing beautiful piano for over a decade.

Learn More »Piano lessons are sort of like braces. For a few years, everyone's parents paid a lot of money so their children could contort their bodies (fingers; teeth) and lie about doing something daily that, really, they never did (scales; rubber bands). Both were formative experiences. But while everyone grows out of braces, some people never recover from childhood piano lessons. This is, in part, because true pianists' brains are actually different from those of everyone else. In this series, we've already written about what makes guitarists' and drummers' brains unique, but playing keys is an entirely different beast. Drums are functionally pitchless and achordal, so pitch selection and chord voicings aren't part of the equation. Guitar only allows for six notes at once and heavily favors left-hand dexterity. But piano is the ultimate instrument in terms of skill and demand: Two hands have to play together simultaneously while navigating 88 keys. They can play up to 10 notes at a time. To manage all those options, pianists have to develop a totally unique brain capacity — one that has been revealed by science. Because both hands are required to be equally active for pianists' to master their instrument, they have to overcome something innate to almost every person: right or left-handedness. In most people, the depth of the brain's central sulcus is either deeper on the right or on the left side, which then determines which hand is dominant. But when scientists scanned the brains of pianists, they found something different: Pianists had a demonstrably more symmetrical central sulcus than everyone else — though they were born right or left-handed, their brains barely registered it. Because the pianists still had a dominant hand, researchers speculated that their equal depth was not natural, but resulted because pianists are able to strengthen their weaker side to more closely match their dominant side. Rachmaninoff would be proud: Already, then, pianists are able to make their brains into better-rounded machines. But it turns out the heavy-tax of piano playing makes their minds efficient in every way. A study by Dr. Ana Pinho (whose name kind of explains her research focus) showed that when jazz pianists play, their brains have an extremely efficient connection between the different parts of the frontal lobe compared to non-musicians. That's a big deal — the frontal lobe is responsible for integrating a ton of information into decision making. It plays a major role in problem solving, language, spontaneity, decision making and social behavior. Pianists, then, tend to integrate all of the brain's information into more efficient decision making processes. Because of this high speed connection, they can breeze through slower, methodical thinking and tap into quicker and more spontaneous creativity. But piano is a taxing and complex instrument for the whole brain. Real pianists are marked by brains that efficiently conserve energy by allocating resources more effectively than anyone else. Dr. Timo Krings scanned pianists' brains as they soloed and found that they pump less blood than average people in the brain region associated with fine motor skills. Less blood flow means less energy is needed to concentrate. Though that's likely true of anyone who's mastered a nimble task, it only compounds the efficiency pianists' brains develop through mutating the central sulcus and altering their frontal lobe's function. In pianists, the change in blood flow frees them to concentrate on other things that are totally unique to pianists — like their own unique form of communication.

Read the fingers on a piano score Today's sheet music often shows the finger numbers to be used at the location of each musical note. Each note on...

Read More »

Practising needs to fit in around your routine as much as possible. We usually recommend 15 minutes every couple of days when you start out. It...

Read More »It's a difficult concept to grasp, but it's one of the coolest things about being a pianist. When pianists improvise, the language portion of their brain remains active — like any musician, playing music is fundamentally an act of communication. But the big difference for pianists is that their communication is about syntax, not words. Dr. Charles Limb's study showed that when pianists solo, their brains respond as if they were responding in a conversation, but they pay attention to phrasing and "grammatical" structure instead of specific words and phrases. So pianists' brains actually are different. They are masters of creative, purposeful and efficient communication because of the very instrument that they play. They are the naturally efficient multi-taskers of the musical world, because when you're a player like Yuja Wang, there is zero room for doubt and hesitation.

According to Sannes, “Cocomelon is so hyper-stimulating that it acts as a drug, a stimulant. The brain receives a hit of dopamine from screen-time,...

Read More »

Real yellow brick roads One account says it is a brick road in Peekskill, New York, where L. Frank Baum attended Peekskill Military Academy. Other...

Read More »

Angus' picks are made by the Fender 351 Extra Heavy model. The strings used by Young are Ernie Ball Slinky strings (0009-0402) and Fender Extra...

Read More »

Beethoven first noticed difficulties with his hearing decades earlier, sometime in 1798, when he was about 28. By the time he was 44 or 45, he was...

Read More »